China’s art playground: The 798 Beijing art district

From old factory area to a hip and modern district: The 798 Beijing Art District is the new place-to-be for all artsy Beijingers and tourists visiting the Chinese capital. A place, where art meets commerce and calm chimneys pimp flourishing boutiques.

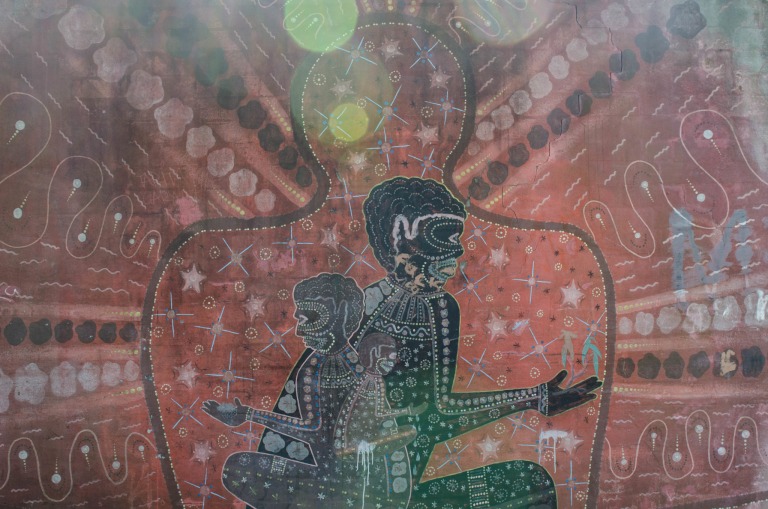

Grinning Mao’s, pillar box-red dinosaurs and heavily pregnant clay-warriors stand about in a bemusing assembly. Built in the 1950’s as a sort of Bauhaus-inspired factory complex, the 798 Beijing Art District is becoming more fashionable than ever. The district has undergone a spectacular shift – transforming itself from a mundane industrial park into a hive of studios and a mecca for China’s modern art scene. Situated north-east of the city centre, 798 is full of galleries, design shops, cafés and hipster-tourists. All year round, this district boasts enough installations and exhibitions to satisfy the endless waves of visitors with works from China’s latest art stars, alongside those of stalwarts such as Ai Weiwei. The line between culture and commerce is increasingly blurred.

The first views are of a row of brick walls. Only here and there is the monotony marred by an occasional slogan or painted image. Huge steel constructions run along above the walls. Beyond them are massive metal gates, tarnished by decades of rust and overgrown train tracks, upon which goods carriages no longer travel, unreadable signs which have long since outgrown their purpose and chimneys, which no longer smoke.

798 Beijing Art District: a synonym for culture and art

The 798 Art District lies in a part of the city called Dashanzi which, during the time of Mao Zedong, functioned as an armaments factory for the Chinese government. This was the product of a military collaboration between the People’s Republic of China and the former Soviet Union, and its official name was Factory 718, in keeping with the Chinese government’s tradition of naming all military installations with a number beginning with ‘7’. The symbolism of this may well trace its origins to the fact that the pronunciation of the Chinese word for seven is close to that of the word for ‘emergence’, or even, of ‘life’s essence’.

Experts from the former East Germany were also involved in the construction of this gigantic industrial complex. The shared goals of Communism were ambitious, after all. In addition to the electronic factories, the site also included living quarters for 20,000 workers– many of these in the Bauhaus style. On this site, an area so large that it resembled an entire district, people worked and laboured for decades. Then Mao died, and an era ended. A time of reform, China’s ‘opening up’ to the outside had begun. Many large-scale, state-owned operations were shut down during this period as the country moved towards a market economy, and at 798, as elsewhere, many former factories stood suddenly empty.

It was during this time that the contemporary arts scene first became established. Initially as an underground movement, later as a more open collective.

The transformation of Chinese society and associated problems became key themes at a time when hopes for a new sort of freedom were beginning to emerge. From the start, Beijing was at the epicentre of a cultural movement that was largely devoted to the exploration of these themes. And from the mid-1990’s, Dashanzi became the beating heart of a fast-growing alternative art scene, the 798 Beijing Art District. Landlords sought tenants but found artists. For this new crowd, the abandoned old factories with their saw tooth-shaped roofs were in fact ideal. They loved the slightly remote location, far from the centre of the city centre, and welcomed the cheap rents and spacious, light-filled rooms. In no time at all, a bohemian assortment of studios, cafes and galleries began to spring up, like as many mushrooms in the autumn. Out of the old, abandoned industrial site, a thriving artistic scene took shape. Not chic, but Industrial Chic. As raw and as real as the artists wanted it to be. They also endeavoured to preserve the antiquated infrastructure around them. Thanks to the initiative of some around Huang Rui, the old numbers which had once served as street names were preserved and the red painted slogans on the walls, dating from the time of the Cultural Revolution, were duly protected.

More than 20 years have now passed and the original workshops, alongside the various galleries and design shops, have evolved into a flagship cultural destination. At the entrance to the exhibition space at the 798 Beijing Art District, one is almost reminded of an amusement park. Many streets are decorated with oversized statues, sculptures and other manifestations of contemporary art, the walls are covered in colourful graffiti and other art installations. One moment, one finds oneself towered over by an immense Tyrannosaurus Rex, formed from a towering 30m mound of steel, and a moment later, a huge mirrored rabbit appears around a corner.

Inside the galleries themselves, Chinese art is not hiding itself away from the international scene. From paintings to multimedia installations and Performance Art, 798 Beijing Art District is booming. But the sheer volume of visitors has hastened the spectre of commerce.

This new economic element is particularly evident in the proliferation of restaurants and cafés in the Beijing 798 Art Zone. Most sell international-style food at higher-than-average prices: from quinoa salads to crushed avocado on rye. As for the art? It is much less underground than it once was. On the contrary, many galleries sell work direct to the public.

A completely unique urban space

Recently, an auction house has even been built, a modern edifice which, from the outside at least, bears little relation to its surroundings. Take-away art is also available from countless little gift shops, which offer postcards, key-rings and other souvenirs. Housewares and avant garde clothing are also available here. Galleries have become boutiques and the 798 art quarter is suddenly a hip sort of shopping centre, a place to spend a Sunday afternoon with friends. On the weekends, one can barely see the art at all for the crowds.

This encroaching commercialisation has long since attracted its critics. For some years now, soul-searching debates have sought to pin down the true purpose of 798 Dashanzi. A number of galleries and artists have decided to depart altogether, with most heading North-East towards Caochangdi. A place where they can focus on their art once again, unhindered by commercial distractions. Chief among them is the Enfant terrible of China’s art scene: Ai Weiwei. This Chinese artist, dissident und latterly new-Berliner launched four new exhibitions in 798 and Caochangdi respectively, shortly after regaining his confiscated passport from the Chinese authorities in 2015. Staging a show would have been unthinkable for the artist just four years earlier, when he was arrested by the authorities for supposed financial offences. Whilst works produced by Ai in his old Beijing studio had been exhibited for years in numerous galleries and museums worldwide, such as Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau –never before had he exhibited in China.

Some of his earlier colleagues defied the lure of the markets and remained in 798. This raises a question about whether unengaged, authentic art can really survive in such a mass-market environment. Only time will tell.

Ai Weiwei is back at 798 Beijing Art District

At least one thing is unbreakable: the raw charm of the armaments industry. This is echoed in the old pipelines which traces their way throughout the site, as in the disused chimneys and forgotten bricks. These relics of a lost, labouring past have become the hallmarks of a flourishing cultural quarter. China has definitely asserted itself in the international art market, whether in 798 or in Caochangdi, and is freeing itself from the conventions of the past. At least, until the wheels of gentrification turn once again.

No comments yet.

Be the first to comment on this post!