The Panjiayuan Antique Market: Beijing’s treasure chest

In a city brimming with history, Beijing’s Panjiayuan flea-market reveals a host of insights into the minutiae of the past.

Mao stands firm: his right arm raised in a perpetual greeting, his bald patch gleaming in the morning sun. The potency of his image is undiminished. It is 8 o’clock in the morning in Beijing and China, the middle kingdom, is already wide awake.

In Chaoyang, an area often regarded as the centre of the city, the streets are bustling with activity. The third eastern ring-road is full of traffic, each car horn seemingly louder than the next. All manner of vehicles jostle for position, from late-model Teslas to the strikingly green-yellow taxis of the 1990’s. And there, alongside it all, workers on their bicycles swerve vulnerably beside the melee, seemingly oblivious to the honks and furious gesticulations of the taxi drivers surrounding them.

This is Beijing, as it lives and breathes. And the morning chaos surprises no-one, not even the city’s most recent arrivals. Beijing today is home to a large and ever-growing contingent of expats, many of them from the West.

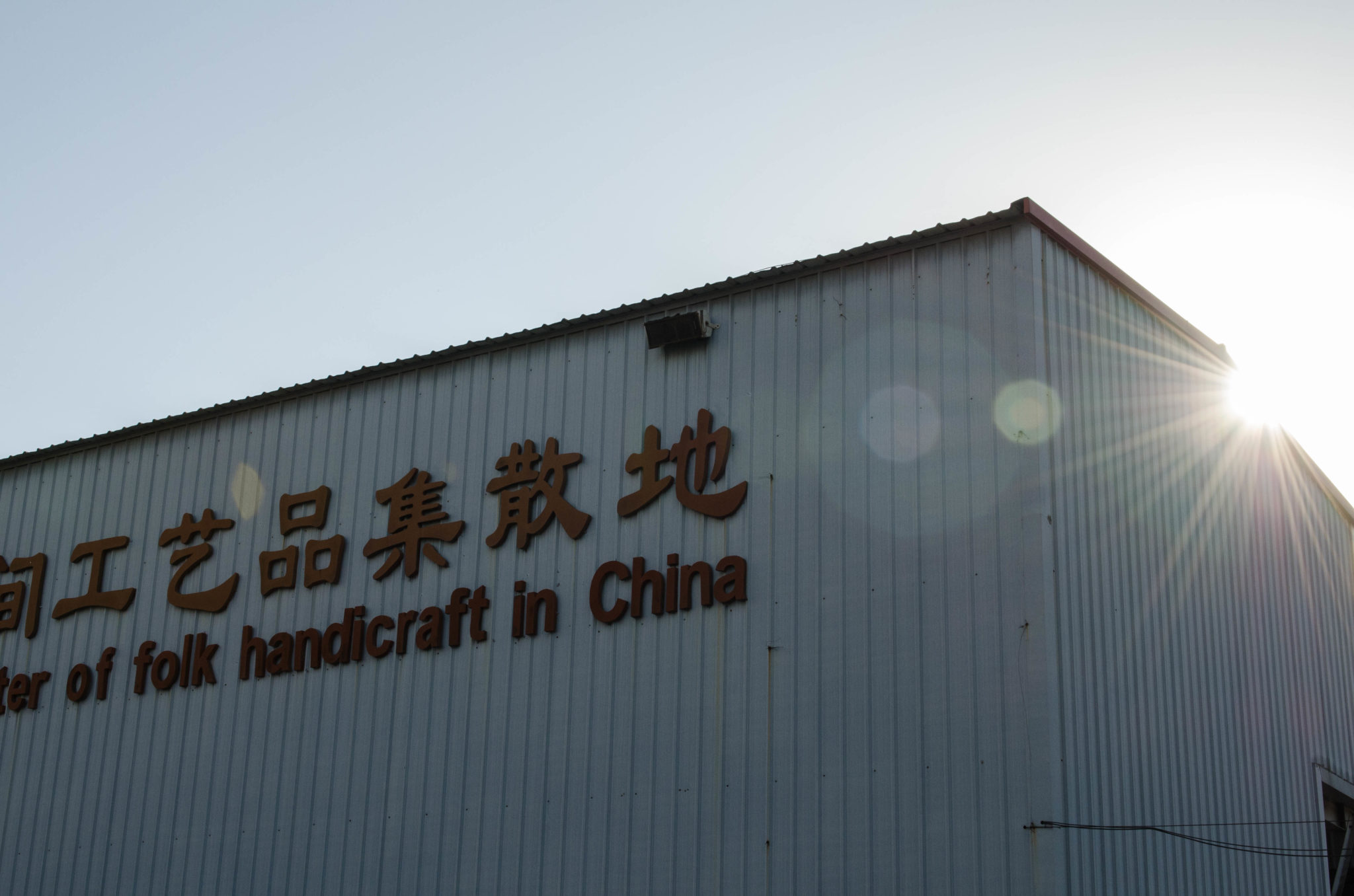

Mao stands beside the road behind a heavy metal gate bearing oversized Chinese characters. Directly beneath is an English translation, or at least, what passes for a translation when cobbled from our 26 available letters. To the Chinese, this paltry figure – 26- must seem almost laughably inadequate.

Our figure of Mao, here in the Panjiayuan antique market, has been cast from bronze and stands at just ten centimetres tall. And he is not alone in his greeting. Hundreds of clones are scattered throughout the market: large and small, cast from bronze, gold or iron. The same unmistakable image has been printed on paper, frequently in poster size. Mao Zedong, the ‘Great Chairman‘, continues to be revered as a saint here in China, and the Panjiayuan antique market is no exception. Beijing is bursting with highlights: the Temple of Heaven, the Summer Palace, Tian’anmen square and the Forbidden City. But in a city which hosts a treasure trove of Chinese history, the Panjiayuan antique market conceals a hidden corner of wonders. A stroll through its narrow lanes lined with semi-improvised stalls transports the visitor at once to another time, another century. Modern Beijing, with its chic shopping arcades, futuristic buildings and multi-lane expressways seems to disappear altogether. Even the endless noise of the traffic seems suddenly distant and barely audible.

Blankets and sheets are spread out across the paved stone floor and various collectables are carefully displayed upon them. These include old, possibly even antique objects, arts and crafts, jade and jewellery, musical instruments and handicrafts.

This 48,500 sqm flea-market is no longer an insider’s secret tip– neither among locals nor tourists. Domestic and foreign tourists alike are busily grappling for bargains in this small corner of Chaoyang. The Panjiayuan antique market is the cheapest antique fair in Beijing – and this sort of reputation travels quickly.

Original or fake? A perfectly normal question, which generally elicits little more than a weary smile. The language barrier appears to stand firmly in the way of any more clarifying response. The impassive faces of the sellers are rather reminiscent of those statues which surround. Perhaps the daily cycle of haggling takes its toll. There are some 4,000 stallholders throughout the market, around 60 percent of whom have come from far-flung provinces and regions, from central China to the outermost fringes of Mongolia.

On one stall, beside a muddle of mandolins, whose advanced age is suggested by the timbre of their wood, stands a selection of reproduction furniture in the Old Chinese style. Some appear so authentic, they could almost have come from Mao’s own palace. Who knows, perhaps they even did?

Nearby, a young and tidily dressed young Chinese man is expressing an interest in a calligraphy set known in China as the ‘Four Treasures of Study‘. This consists of a brush, ink, manuscript paper and an ink-stone, lovingly encased in a leather pouch. It certainly looks beautiful – and old. Little wonder, that the young man is so captivated by it. However its value is apparently rated even more highly by the seller, whose optimistic asking price sends the potential buyer scurrying away into the market, shaking his head in dismay. When did old things become hip enough to attract such horrendous prices?

The seller on the adjacent stall is having more luck. A middle-aged woman is busily rifling through a box of ancient Chinese coins. Are they new, or imitation? Irrespective, they are certainly pretty – and would look delightful in a living room showcase. She selects a dozen favoured examples and pays for them with a satisfied smile. The stallholder is happy to reciprocate: after all, in China, every good market day begins with a good deal – since time immemorial.

Panjiayuan flea-market was first established in the 1980’s by a small collective of traders in a simple Hutong, the traditional Beijing housing development. Hoping to supplement their incomes by raising a little spare cash, a handful of residents decided to set up an improvised collection of outdoor stalls on the weekends. In those days, most of the items sold were artworks from their family homes. The trade in such objects was still strictly forbidden under Chinese law. As a result, Panjiayuan quietly grew as an underground exchange for every manner of antiques, a ghost market which Beijing’s police would declare they knew nothing about.

The little black market grew at an astonishing pace, gradually evolving into a proper antiques fair that proved so popular among Beijing’s art-lovers, that the stallholders were forced to increase the parameters of their market. An expanded area was established in a forested district near Panjiayuan Bridge. As time went on, ever more sellers arrived from the impoverished provinces, hoping to make their fortunes by selling their rural collectables to the Beijing public. Simple farmers were transformed into art dealers. After centuries of family ownership, rare antiques were exchanged for intensely-haggled sums. The daily bustle of the flea-market was benignly tolerated by local authorities for many years, until the trade in art was finally legalised in 1994. Just a year later, they offered the smallholders a proper space for their market, and Panjiayuan in its current form was born.

More than 20 years later, childish laughter echoes through the stalls. In one of the narrow aisles, to little boys are trying to scare each other with masks from a Chinese opera. They explode into giggles. The scene has a sense of window-shopping spontaneity about – like trying on a hat, or pair of sunglasses, which one has no intention of ever buying. The masks are returned to their places under the watchful eye of an unimpressed stallholder and the boys move on. Whether the objects on sale are genuinely old or merely clever reproductions, Beijing‘s Panjiayuan antique market underscores one thing: the growing interest in Chinese folk culture. And this comes across very well.

In amongst the bustle of locals and uncertain tourists, Mao statues appear time and again. The recurrent bald patches now gleam in the late afternoon sun. Could the great Mao Zedong have ever imagined that his image would one day proliferate in a Beijing flea-market? The thought would probably have appealed to him.

No comments yet.

Be the first to comment on this post!