Türkiye: Wrecked by Hate But Standing Strong

A pilgrimage site for Christians and Muslims alike: The Sumela Monastery on the Turkish Black Sea coast differs opinions for centuries. A confrontation that left its mark on the ancient walls and in the locals' hearts and minds.

Poor Peter is missing an arm, Mary needs urgent plastic surgery and even Jesus would look out of place without his wounds. Most religious portrayals are disfigured, from the Three Kings to the Sermon on the Mount. Everything looks like a stage for the end times to play out on, but that’s not actually the case. The Sumela Monastery stands 1200m in the sky, far on the other side of the classic tourist trail and on the Turkish coast of the Black Sea, between Istanbul and the coastal town of Trabzon. From there, an unassuming winding road leads up a narrow mountain pass, past the city of Maçka, until it reaches Mela Mountain in Altindere National Park. Only after the last curve does Sumela Monastery rise before the eye of the beholder, like a holy apparition. As if immersed in silent prayer, the old ruins are embedded in the steep slopes, surrounded only by the endless see of pines of the Zigana mountain range. The scene is slightly surreal, reminiscent of the enchanted mountain monasteries of Bhutan.

The Black Sea region of Turkey still needs to fight for every single foreign tourist. The competition from popular holiday destinations like Antalya and Side on the idyllic southern Mediterranean coast is too strong. Those who dare to go to the eastern end, though, are bound to come across forgotten treasures.

A monastery with history

The Sumela Monastery is one of the brightest gems. The story of the monastery’s foundation has become a legend: an icon of Mary, painted by Luke the evangelist himself, was carried here through the clouds by two angels and put in a cave. Two monks called Sophronios and Barnabas decided to create a site worthy of housing it. This building was commissioned by Emperor Anastasios in 500, but only became a place of pilgrimage centuries after the Ottoman conquest in 1461.

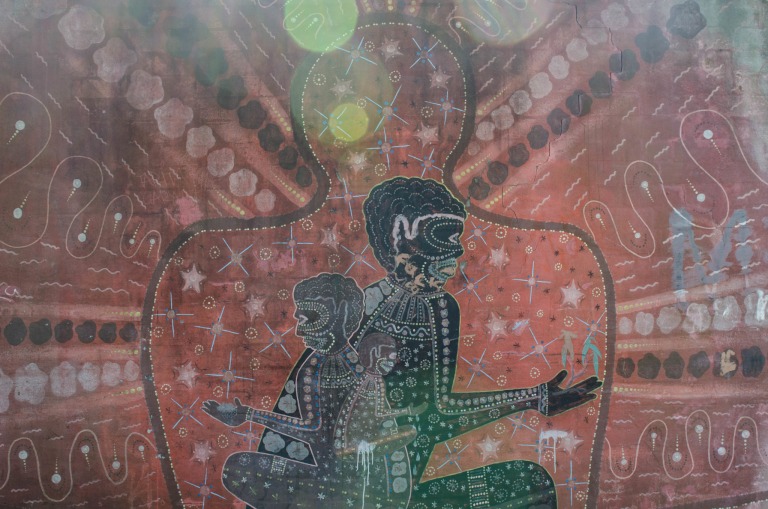

The monastery’s current appearance stems from the 19th century, when the bustling monks built prayer and sleeping rooms from stone in front of the rock church. From time to time, pilgrims consorted with the monks. In order to bring the Bible message to these people, who were often illiterate, its holy walls were painted with frescoes.

It is likely the monks’ dedication and the seclusion of the monastery that allowed the paintings to withstand centuries of fire and attacks from vagabonds.

After the First World War, when the Greek population tried to found their own republic, they had to reckon with Atatürk’s troops. The monks were also persecuted and elft the country in droves.

A monastery carved into the rock is there for good

What remained was looted, which left only one thing behind: the frescoes on the walls. But these, too, soon faded into obscurity, left to decay. Today, 100 years later, the monks sometimes return. One or two travel buses are parked below the monastery. Since the Turkish government put it under preservation status in 1972, it has been attracting mainly local tourists, including Muslims. They call it “Meryem ana manastiri”, too – Monastery of Mother Mary. This Mary is honoured in Islam as the mother of the Prophet.

Go up the long, narrow, torturous stairs to the entrance and you’ll end up in the middle of a true masterpiece made of stone. The bell tower is standing there in all its glory and the picturesque holy fountain and pretty chapel can still be made out. Mostly, though, the countless frescoes stand out.

Detailed representations of holy people, apostles and entire scenes from the Bible are on the rocky walls. Paintings that have been forgotten over the centuries and left to the elements – and, unfortunately, humanity, apparently.

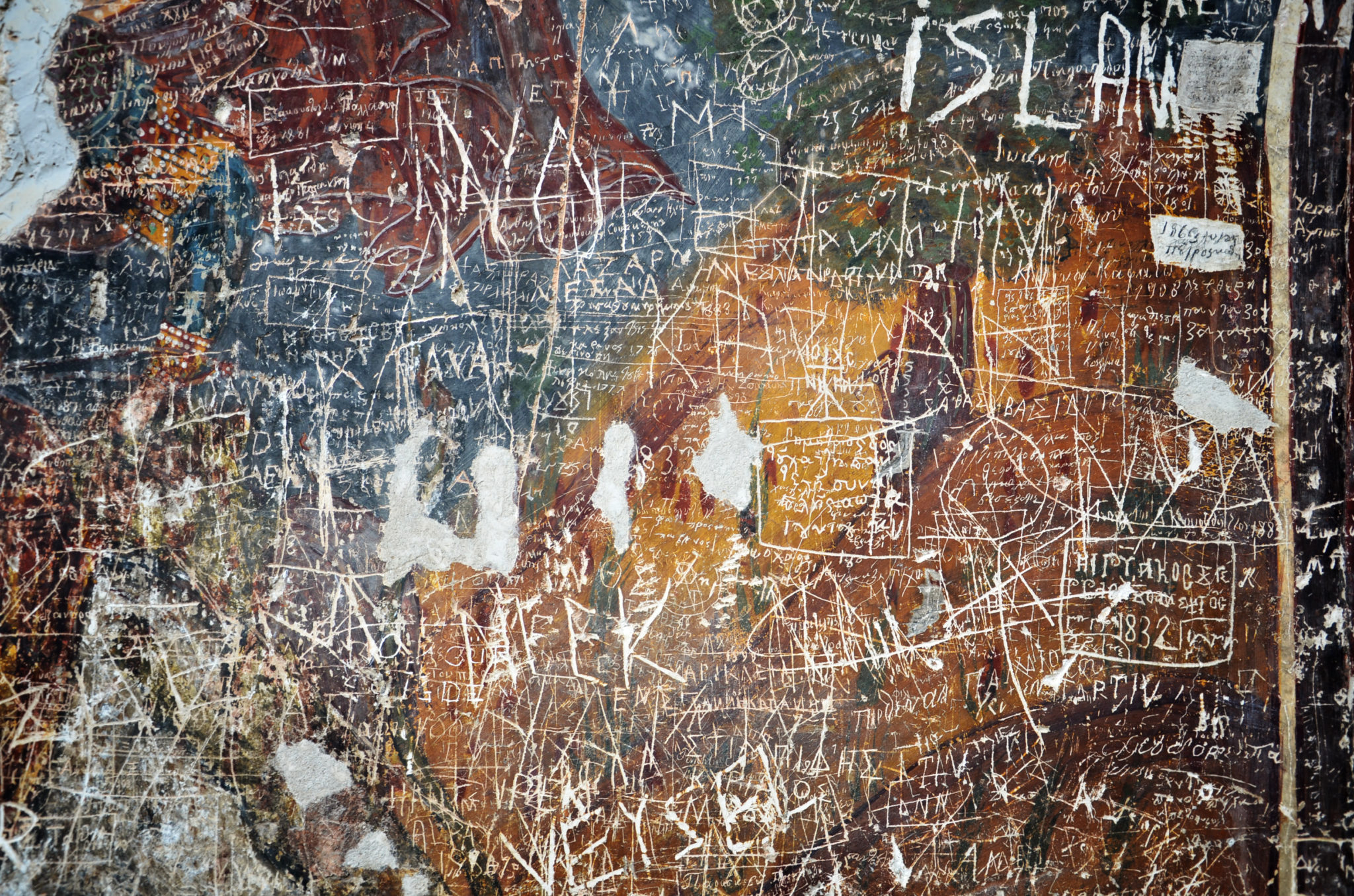

Vandalism from 1600 years ago

The worst destruction has been committed by wall peckers and souvenir hunters. In parts, you can even see names and dates scratched carefully into the stones. Under the likeness of Jesus Christ: “Tom was here”. Next to it is a little heart: “Emre loves Aylin”. Good to know.

From the goat herder to the fisherman: since the monks turned their back on Mela Mountain, many appropriated the holy walls to leave their traces behind. Even the strictest atheist would be horrified when looking around. The sign says “Graffitiing the walls is an offence” – a warning that came a few centuries too late. But you also notice that entire faces are scratched out, half the Bible stories ripped out of the walls. It seems as if someone was angry with Christianity, but where does all this hate come from? Theories are divided, moving between targeted religious desecration and the thoughtless vandalism of modern freethinkers.

There is a glimmer of hope on the search for answers about the scratched-out frescoes hope, though. Regular services have been taking place here for a few years, overseen by the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomeos I.

Hateful destruction or youthful folly?

The Orthodox Christian pilgrims come in their thousands in each year, and so do Muslims. Hand in hand, they celebrate Christianity and Islam, in a place that couldn’t be more contradictory. Sumela Monastery has become a meeting point for religions. In the evenings, when the fog slowly sets into the pine forest, the last day tourists go off again. On the way to the car park, they pass a small souvenir shop, selling what souvenir shops at Christian pilgrim shops normally sell: candles, statues of the Virgin and portrayals of Peter, Mary and Jesus. Holy medallions, too – free from scratches and declarations of love.

No comments yet.

Be the first to comment on this post!